When former Vice President Kamala Harris announced in July that she was not going to run for governor in 2026, it was a jolt to every ambitious politician —and aspiring politician — in California. Suddenly, the race that was hers to lose was wide open.

Sure, there were some notable people already running, such as former Rep. Katie Porter, former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, former state Senate leader Toni Atkins and Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalakis (the latter two have since dropped out), but none had caught fire with voters yet. So, with no frontrunner, Democrats and Republicans jumped into the race in droves.

Now, just two weeks until the filing deadline for the June 2 primary, none of the 11 prominent candidates have broken through. California’s next governor could be among the least qualified of the group or a MAGA Republican. Or both.

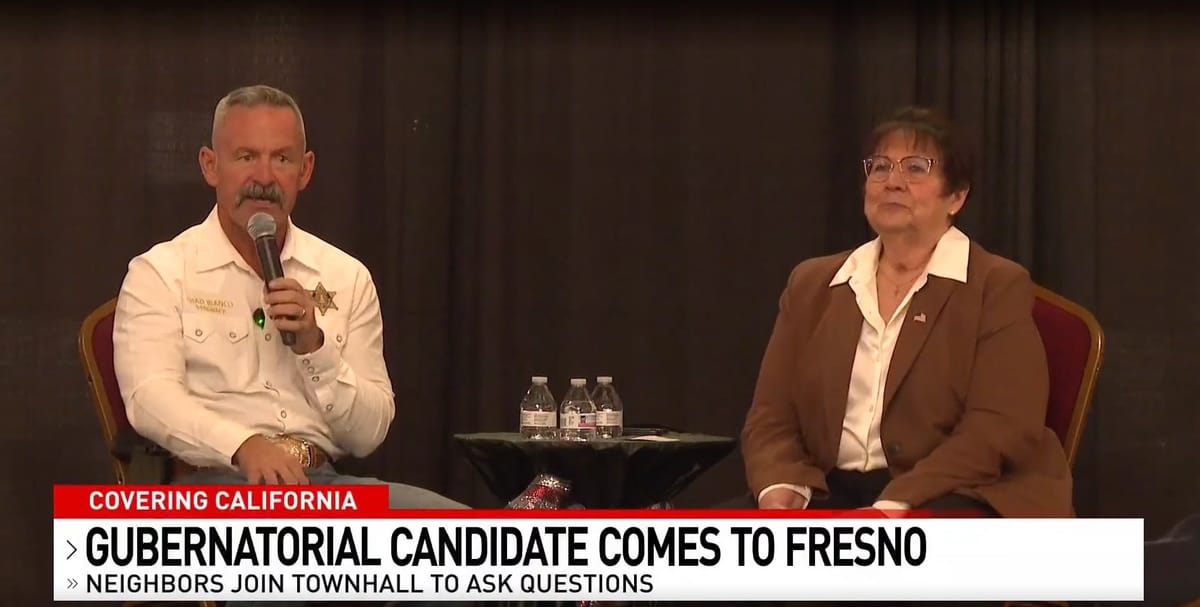

That’s the downside of California’s mostly commendable nonpartisan primary system, in which the two candidates with the most votes advance to the general election regardless of party. An Emerson College poll released earlier this week found that two Republicans — former Fox News commentator Steve Hilton, a British-born California resident who has never held public office, and Riverside County Sheriff Chad Bianco, a strong Trump supporter — are among the top three candidates favored by likely voters, 17 percent and 14 percent respectively.

Those aren’t big numbers, which is normal with so many candidates. Collectively, Democratic candidates have more support. But that won’t mean squat if their voters are scattered among eight midlevel candidates with distinct fan groups. And frustratingly, none appears inclined to drop out over their poor showing so far, even if it means trouble for their own party. Egos!

It could be that Bay Area Democratic Rep. Eric Swalwell, who polled among the top three at 14 percent, is able to break through the pack. U.S. Sen. Adam Schiff has endorsed him, and if another House colleague, former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, does the same that could give him a big boost. But that doesn’t make him the best candidate, just the one with the better shot at advancing into the general election.

Golden State is a member-supported publication. No billionaires tell us what to do. If you enjoy what you're reading, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription and support independent, home-grown journalism.

This dicey situation is not Harris’ fault. She has every right to chart her own future. But I wish she would change her mind and get back in the race.

Harris probably still has her sights on the presidency. She came so close in 2024, even with just 107 days to campaign and carrying all of President Biden’s baggage. Still, there are at least three good reasons for her to reconsider California’s top job:

It’s a pretty good gig. It’s true that the president has the most powerful job in the country, if not the world. But I submit that the second-most powerful political position in the country is the governor of its largest state.

Under Gov. Gavin Newsom, California has emerged as a sane counterpoint to the dark and repressive regime in Washington. If Harris succeeds Newsom, the Golden State will continue to be a beacon for disaffected, disheartened Americans worried that the country is slipping into an era of authoritarianism.

Sure, the state has its challenges – homelessness, unaffordable housing, devastating wildfires – and not enough revenue to pay for all of its promised services. But running California can’t be any tougher than leading a divided nation.

It’s a sure bet. Or at least a surer one than the 2028 presidential primary. At the moment, another Californian, Newsom, is the unofficial Democratic frontrunner, and it’s impossible to know what the political situation will look like in two years. Why risk it?

If Harris joins the governor’s race, many of her fellow Democrats will step aside in respect — and recognition that they don’t have a shot against her. A Republican will likely come in second, as usual, which means Harris is all but guaranteed to win in November.

She’s the most qualified candidate. Nobody in the race has a CV even close to hers. In addition to being vice president, Harris was a U.S. senator. But it’s her experience running a state agency, as California attorney general that best prepares her to lead the state’s massive government. Only two other candidates have done that: Xavier Becerra, who was appointed attorney general when Harris won her Senate seat in 2016, and Betty Yee, a former state controller.

Harris could make a convincing argument (she’s a prosecutor, after all) that her reversal does not indicate indecision or fear about her prospects in the 2028 presidential race.

Rather, it’s a manifestation of her sincere concern that the surplus of Democrats in the race means her home state could fall into the hands of Trump-supporting Republicans who don’t share the liberal-leaning values of most Californians.