Jon Regardie is a veteran Los Angeles journalist who has contributed to dozens of local and national publications, including L.A. Downtown News, where he served as editor, and Los Angeles Magazine, Blueprint, Westside Current, The Eastsider and Crosstown.

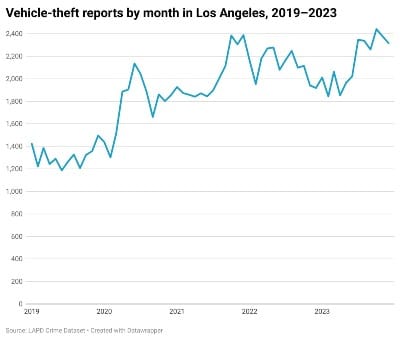

In a November 2023 story for Crosstown, I wrote about soaring car thefts in Los Angeles and the neighborhoods victimized most frequently. Crosstown is a nonprofit news organization based out of the USC Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism that mines publicly available data to produce original stories. Using data from the Los Angeles Police Department, I identified spiking counts in downtown L.A. (1,305), Westlake (662) and so on.

That was the tip of an information iceberg. The Crosstown staff and I used the LAPD data to report that catalytic converter theft had recently dropped off after a sudden spike and arson incidents were lower than the peak in 2020. We were able to pinpoint eye-opening, neighborhood-specific news, such as an eightfold surge in shoplifting in Sawtelle and a rash of gunshots in San Pedro.

However, those kinds of stories have been impossible to report in the two years since we completed the 2023 report. A molasses-slow shift in how the LAPD assembles and presents public data has severely limited Crosstown’s, and Angelenos’, knowledge of what sort of crime is occurring in the city’s neighborhoods. Upgrading to the new data process, which began in March 2024, was supposed to take six months. It is now more than a year behind schedule, and the department won’t say when full access to public data — our data — will be restored.

The dearth of data hinders transparency, and means members of the public have no real sense of how well crime suppression is working at the neighborhood level. They have no idea, for example, if their neighborhood is experiencing a month to month or year to year rise in burglaries or car break-ins, information they could use to demand action from their senior lead officer or help from their local council office.It’s not just crime, either — the LAPD’s traffic collision dataset stopped updating earlier this year. While Crosstown was previously able to break down traffic deaths by neighborhood — downtown, Sun Valley and Manchester Square topped the list of fatalities in 2023 — now that can’t happen.

This is problematic in a city where vehicular deaths exceed homicides, and as Golden State just noted, the Vision Zero effort to eliminate auto-related fatalities has been an abject failure. With functioning data we could detail which neighborhoods record the most pedestrians struck, or where the highest number of DUIs occur.

If you like this story, sign up for the Golden State Report newsletter to get news analysis and commentary delivered to your inbox twice a week.

Some information is available. The LAPD publishes weekly Compstat reports on major crimes such as homicide, robbery and larceny that include the current year’s count and the year-over-year change. There’s a citywide Compstat report, and versions for each of the department’s 21 stations.

There’s also a weekly traffic collisions report, which shows counts of injuries, fatalities, felony hit-and-runs, etc.

Those reports are informative but shallow. The raw data were much deeper.

Part of the frustration is that, for a long time, the LAPD did a better job than most law enforcement agencies at detailing what was happening. In 2010, the department began providing information on each of the more than 200,000 crimes reported in Los Angeles annually, from battery to bike theft (it’s worth noting that not every crime gets reported, sometimes because victims don’t trust police).

The online dataset offered an ocean of information, with columns and numbers that can cause eyes to glaze over. But within the crime codes, weapon codes, and latitudes and longitudes, there’s a gold mine of actionable information for anyone with the patience or software to find it. At least, there used to be.

The LAPD stopped updating the detailed online data when it began transitioning from the crime reporting system it had long used to a modern version instituted by the FBI, the National Incident-Based Reporting System, which advocates say provides deeper, more accurate crime information than what had been available before.

It was supposed to take about six months for the department to fully implement the new system. But 21 months later, some crime data is clearly missing. For example, the NIBRS dataset lists about 12,250 crime reports in Los Angeles in September 2025 compared with 19,300 in the same month in 2023. Either crime fell a whopping 37 percent in two years, which seems unlikely, or incidents are not reaching the dataset. Additionally, the Los Angeles NIBRS data does not show where the crime occurred, which is crucial information for neighborhood watch and community groups.

When I asked LAPD’s public information office what was happening with the data or why things were taking so long, I could not get an answer. In October, a department representative told a Crosstown colleague that they did not have an ETA for when the full data would be available again. That same month, the LAPD denied a request by LAist.com for similar crime-mapping data, saying it could “lead to misguided public policy discussions or unjustified public panic.”

Another reason this is frustrating is that some city departments are offering better data while the LAPD is going backwards. For example, a recent overhaul of the MyLA311 system means that, for the first time, we know how many Angelenos complain about potholes or beehives (we already had data on graffiti and illegal dumping), and we can identify where the calls are coming from.

Technology is delivering more and more data, providing information many people never thought possible. And what could be more useful for Angelenos than knowing what kind of crime is occurring in their neighborhood and on their block?

It’s understandable that the complex process of installing a new reporting system would take some time. Department command staff told the Police Commission in 2024 that the data shift was part of a complete overhaul of LAPD computer systems that dated to the 1970s. “It’s a huge transformational change” for the organization, then-Deputy Chief John McMahon told the commission.

Importing millions of existing crime reports into a modern system is a heavy lift. Then again, LAPD staff had consulted with personnel in the New York City and Philadelphia police departments who had already successfully completed a NIBRS transition. That made them enthusiastic about what would come.

“Crime analysis moving forward will be far more robust, far more accurate, and we’ll be able to report to the community in far more detail what’s going on,” McMahon told the commission in 2024.

But nearly two years on, that promise has yet to be met.